Just One Dollar

October 23, 2020

Hugo Christian-Slane

Hugo Christian-Slane is a multi-award winning designer and conceptual artist from New Zealand currently living in New York. His latest series, Just One Dollar, explores the value of currency and commerce and challenges Western spending habits and ideals.

My ideal New York “art-world” is one that relies less on larger institutions, galleries, and clients, and instead emphasizes art displayed everywhere, from subways to sidewalks to street posts to even the dollars in your pocket. Accessible styles of art-making empower both creators and consumers, boosting an inclusive and collaborative creative industry. The fine art world at large doesn’t seem to endorse this type of outlook, even as the pandemic has changed how people interact with art and media on a day to day basis. Exhibits might be readily accessible online, but only people living in privilege have the financial security and leisure time to schedule in-person gallery and museum visits.

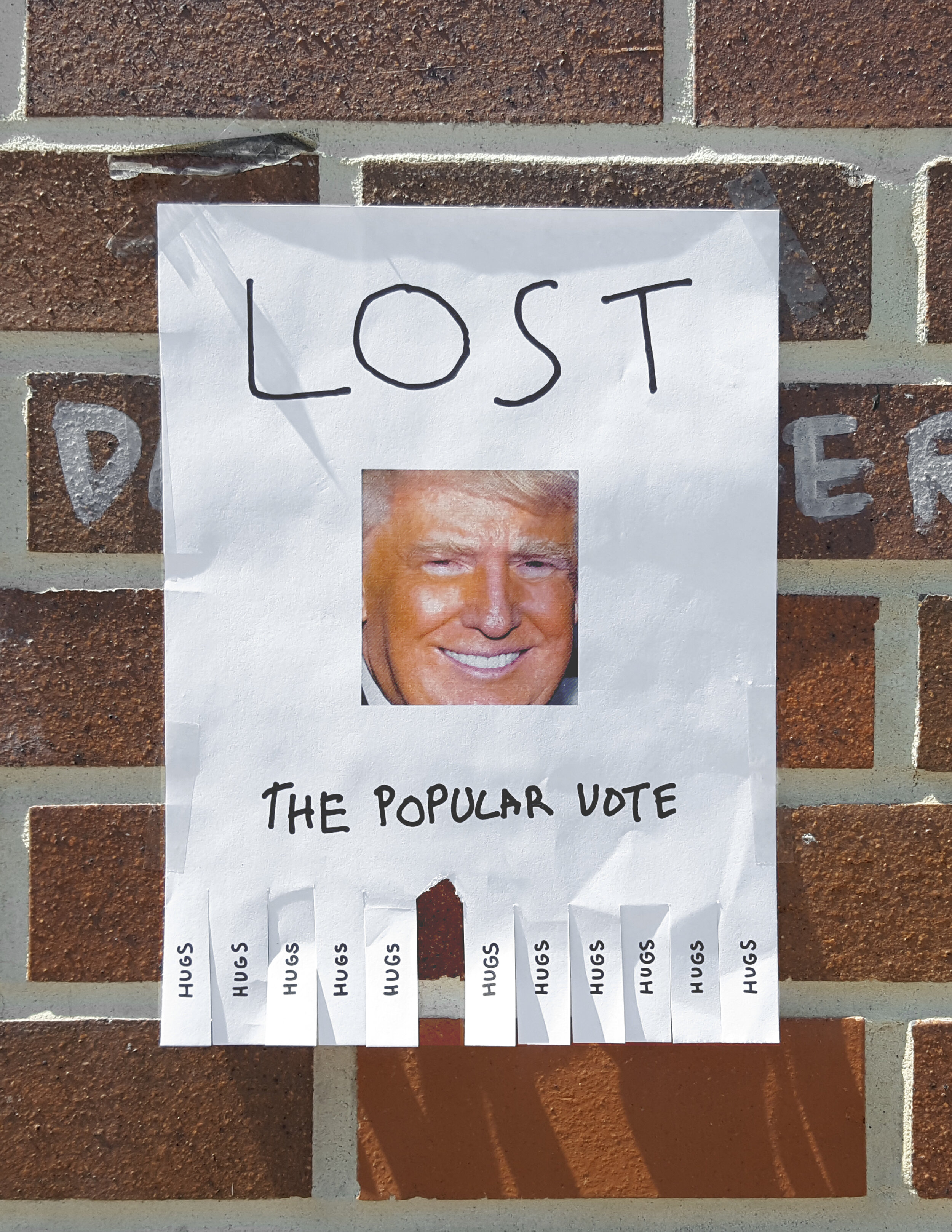

I hope to see my practice take a democratic approach to art creation and engagement. I’m interested in making work that lives in the public space and not within a white-walled gallery. Naturally, if I conceptualize my series around conversations of politics, I want it to be free and available to the public. The experience of making public art allows you to discover and connect with more than just an audience, especially as social media becomes a greater tool for direct engagement with a global community.

I’m interested in making work that lives in the public space and not within a white-walled gallery… Art that belongs to the people feels like the truest form of fine art — not something that belongs to a gallery or brand that intends to profit off the images.

Some of the LOST Posters I’ve thrown up around New York have been noticed by countless viewers, and art critics like Jerry Saltz and even Game of Thrones actors have posted them on their Instagrams. People message me about them all the time. Someone visiting New York from Germany reached out, and I sent him a PDF to repost the works around Berlin because he liked them so much. Frankly, they’re just a bunch of IRL memes — existing images repurposed and remixed with the thematic language of a lost poster; their initial intentions changed to fit satirical methods of storytelling. Because the posters address universal issues that exist in international politics, they are widely understandable and accessible, regardless of the subject matter. For me, art that belongs to the people feels like the truest form of fine art, not anything that belongs to a gallery or brand that intends to profit off the images.

An example of an artist working in this space whom I love is Ahmed Zaino, a Syrian activist who used ping-pong balls to speak out against Assad. He wrote the word “Hurriyah!” (“Freedom!”) on thousands of orange ping-pong balls and tossed them into the streets of Damascus. The following day, people watched as Assad’s soldiers, armed with rifles, hilariously ran around and collected these tiny orange balls.

I’m fascinated with satire’s ability to condense complex ideas into emotionally digestible information or change the way you perceive an oppressive power. My most recent series, Just One Dollar, uses satire to address income inequality and disparity by presenting one hundred $1 bills in one hundred different ways — attaching a different meaning to each individual dollar. My hope is to demonstrate the flexibility of the definition of “one” from person to person, emphasizing the range of meanings and values each person applies to this prevalent piece of paper.

I started by asking myself, What does the phrase, “Just one dollar,” mean to different people? For a person experiencing homelessness, just one dollar could mean a place to sleep or a meal to fill an empty stomach. For a Wall Street banker, one dollar might not be worth picking up from the sidewalk. For a child, it could buy them a can of soda, or the tooth fairy might leave it under their pillow. Money is a funny human construct, one we all believe in and take part in. By highlighting the emotional range of value that people place on money, I hope to encourage empathy and generosity.

I think it’s harder for the working class to throw away a $100 bill because our emotional value for money is magnified by lack of economic security and universal basic income. Global crises like the pandemic highlight people’s needs for financial security and reveal how governments really feel about the working class. Consider how the U.S. government distributed its stimulus checks. Their intent was never to give financial aid to people across the country, but to stimulate the economy. They’ve only just come around to increasing unemployment benefits because more middle-class white Americans are finally affected by the pandemic, not because they wanted to financially support communities of color and lower-income groups.

Money is a funny human construct, one we all believe in and take part in. By highlighting the emotional range of value that people place on money, I hope to encourage empathy and generosity.

For economic security to exist for these groups and the working class, we must challenge a society that makes possible different subjective values for just one dollar. I think we can learn to assess capitalism if we address it on a personal level. Imagine how you would reconsider the ways you spend money if each dollar bill included a tangible, personal message about where it had come from, where it was going, or what you should do with it. Would you pass it over the counter if it told you to “Keep This ONE For Later,” “Spend ONE Less,” “Save ONE More?” What would you do with one that said, “Give This ONE Away?” Would these messages address whether we need to buy that product or not?

A great practice is to question how you are voting with your dollars. Are you supporting businesses and corporations that exploit human rights for growth? A message like “The ONE Percent” might make you reconsider. I would like each dollar to help us question our intent behind our spending. We should question what we do with our money when we have it, how it leaves us, and how and why it stays with us. Why am I buying this? Is this money going straight into the pocket of Jeff Bezos? Or is it returning to the community ethically and sustainably?